Nuclear waste costs Americans billions every year

Q&A with Rodney C. Ewing, co-director of the Center for International Security and Cooperation, a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and a Professor in the School of Earth, Energy and Environmental Sciences. Written with Nicole Feldman.

With the Trump-Kim Summit fresh in our minds, Americans are ready to confront nuclear challenges that have been on hold for decades. What many may not realize is that one of the biggest challenges is on the home front. Since the Manhattan Project officially began in 1942, the United States has faced ever-increasing stores of nuclear waste. In Part Three of our series on the consequences of nuclear war, expert Rodney C. Ewing tells us how the U.S.’s failure to implement a permanent solution for nuclear waste storage and disposal is costing Americans billions of dollars a year.

Where does our nuclear waste come from, and what is being done with it?

Broadly speaking, there are two types of nuclear waste.

The first is spent fuel from nuclear reactors used to generate electricity. Those reactors have left us with about 80,000 metric tonnes of used spent fuel, and we don’t have a way forward for the disposal of this waste. It’s stored at more than 75 sites in 35 states around the country, so many of us have some in our state, including California.

The second category is the waste generated by our nuclear weapons complex. That defense waste has accumulated since the earliest days of the Manhattan Project. The highly-radioactive waste from chemical processing is mainly stored in very large metal tanks. They are located at the Savannah River site in South Carolina, the Hanford site in Washington State, at Idaho National Laboratory in Idaho, and Nuclear Fuel Services site at West Valley in New York State.

I think it’s discouraging that we continue to release radioactivity to the environment because after more than 40 years we still have not developed a successful plan for going forward.

What’s wrong with what’s happening now?

This waste is problematic because the volume is large, many hundreds of thousands of cubic meters. The tanks in Hanford and Savannah River are way beyond their design lifetimes, so they’re corroding and some have leaked. The radioactive fluid is being released to the environment. The rates are not high, but I think it’s discouraging that we continue to release radioactivity to the environment because after more than 40 years of effort we still have not developed a successful plan for going forward.

The spent fuel from commercial power plants is much smaller, some 80,000 metric tonnes, but the total amount of radioactivity is roughly 20 to 30 times greater than defense waste. Today, it’s the spent fuel that demands the most attention as an immediate problem, particularly financially.

How much is nuclear waste costing American taxpayers?

The two categories of waste are separated in the budget. At the moment, the budget for the Department of Energy is about $30 billion. Of that budget, about $12 billion is for the nuclear weapons programs. That leaves us $18 billion to use for all things related to energy — nuclear power, fossil fuel, wind, and solar. About $6 billion, one third, is used to deal with the legacy high-level waste from the Manhattan Project. We as taxpayers pay $6 billion every year to address that problem, a huge cost that we will incur for many decades into the future. The projected total cost of clean-up after the Manhattan Project is well over $300 billion. That’s more than the original cost of the weapons programs and the actual total will be even higher. That’s just the defense waste.

What about the waste from nuclear energy? Is that clean-up cost also high?

In short, very. The Nuclear Waste Policy Act of 1982 created a tax on electricity generated by nuclear power plants. This tax would accumulate into the Nuclear Waste Fund for us to build a geologic repository — a mined facility deep within the earth — to safely dispose of the waste. What’s happened to that?

The fund has a balance of more than $40 billion. It’s controlled by Congress on an annual basis, and congressional budget rules make it very difficult to use those funds. It’s not a lockbox where the money goes and waits to be spent. Instead, it’s been applied against our national debt, so even though the fees have been collected, they haven’t been used for their intended purpose.

We pay about half-a-billion dollars a year to the utilities for their simply keeping the fuel because there’s no place for it to go.

The Department of Energy was to take ownership of this fuel on January 1, 1998, but they didn’t because there was no geologic repository. Now the utilities who have the fuel have to continue to deal with it onsite. They have sued the federal government for its failure to take ownership of the fuel, so now we pay about half-a-billion dollars a year to the utilities for their simply keeping the fuel because there’s no place for it to go. The projected cost of this penalty, let’s say, is something on the order of many tens of billions of dollars, depending on how long the spent fuel has to remain at the reactor sites. The cost of doing nothing over time will be equivalent to what we charge the rate payers, $40 billion over time. That doesn’t even include compensation to workers in defense facilities, soldiers exposed during atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, and so on.

Clearly, the financial cost to taxpayers is high. What about the cost to the environment?

For the spent fuel, the volume — 80,000 metric tons — sounds like a lot, but compared to Gigatonnes of carbon emitted by burning fossil fuels, its volume is not so great. It’s well-contained, but there are some difficulties with how it’s stored. In some cases, the used fuel is kept in pools. Those pools have filled, and they weren’t meant for extended storage. We should be trying to get that fuel into what are called dry casks: obelisks concrete and metal.

Are there other challenges people may not be aware of?

What people don’t realize is that it is actually a serious technical challenge.

It’s very common for people to say there are no technical problems, that it’s just political. They say, “We know how to do it. It’s just a difficult public. Strict regulations. No one will let us solve this problem.”

I think what people don’t realize is that it is actually a serious technical challenge. The half-lives of some of these elements stretch into tens, if not hundreds of thousands of years. We’re asked to design solutions that will last as long as the risk. That’s not something we usually do. The technical and scientific challenge for nuclear waste is, whatever our solution, that we will never see whether we were correct or not. Designing a system where you don’t have feedback is very difficult.

What will happen if we don’t find a solution?

There will not be an immediate catastrophe; I don’t expect anything to explode. There will be environmental contamination, but the biggest problem is financial. We’re spending $6 billion a year trying to deal with the problem, and we’ll continue to spend $4.5 to $5 billion a year without solving the problem. That $5 billion could go to education or research. Imagine if instead of working on waste, we were working on solving our future energy needs.

What’s the best way for us to move forward?

At Stanford, over a two-year period we had a series of meetings to ask just this question: how does the U.S. break out of its gridlock situation and move ahead? We brought in international experts, members of the public, really quite an extraordinary effort, over 75 speakers in five meetings. We have a number of recommendations. We need a new, single purpose nuclear waste management organization. We need a new process for engaging not only the scientific and technical communities, but also the public. We need a new regulatory framework that recognizes the challenges of predicting repository performance over hundreds of thousands of years. Most importantly, we need to realize that dealing with nuclear waste is not only a technical issue, but also requires careful attention to social issues. It is very important to design an approach that engages local communities, states, and tribes. This report, Reset of U.S. Nuclear Waste Management Strategy and Policies, will be released this summer.

Drell, Sakharov, and Panofsky at Stanford,1989

Drell, Sakharov, and Panofsky at Stanford,1989

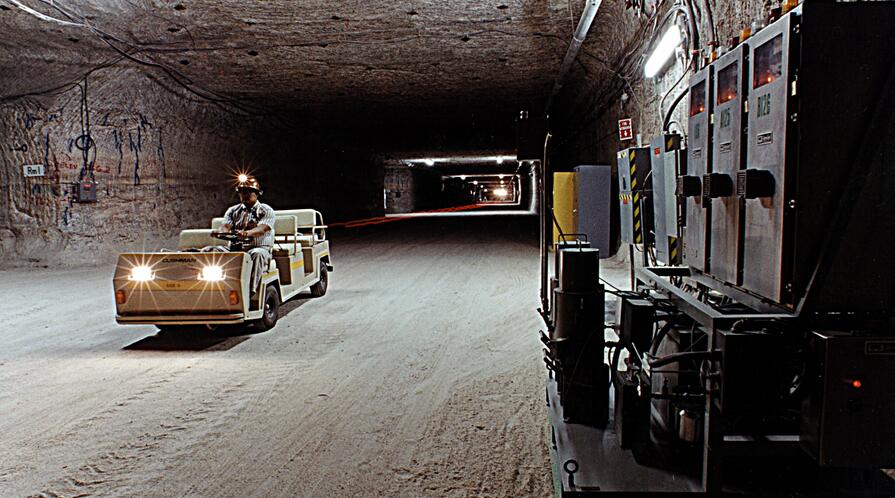

A shipment of transuranic waste from the defense industry heads for long-term storage at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in this photo from 2012.

A shipment of transuranic waste from the defense industry heads for long-term storage at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in this photo from 2012.

Kathryn Shaver from Canada's Nuclear Waste Management Organization listens to a speaker during a steering committee meeting for the Reset of U.S. Nuclear Waste Management Strategy and Policy Series.

Kathryn Shaver from Canada's Nuclear Waste Management Organization listens to a speaker during a steering committee meeting for the Reset of U.S. Nuclear Waste Management Strategy and Policy Series.