Stories of children in Syria's civil war

Stories of children in Syria's civil war

Syria's civil war has taken a devastating toll on children.

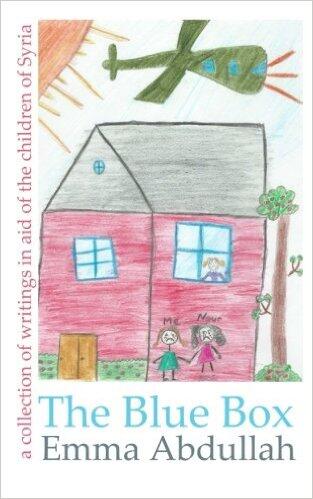

Stanford freshman Emma Abdullah puts a young human face on that tragedy with her book, The Blue Box, which details the plights of Syrian children during the country’s six-year civil war. Published in 2014, the work is a collection of short stories and poems, and all proceeds go to charity. Abdullah estimates she’s raised $80,000 for the cause. Abdullah, who was raised in Kuwait, has relatives and friends from her father’s side of the family in Syria who have died or gone missing.

As many as 470,000 people and 10,000 children have been killed in the war, according to published accounts and the United Nations.

“My goal is to raise awareness about what these children are going through,” said Abdullah, who spoke at a recent staff meeting at Stanford's Center for International Security and Cooperation. “It’s important for me to bring this situation to light.”

She’s found receptive minds among her fellow classmates, though many of them were not aware of the scope of horror in Syria. “Other students have been good, and people are willing to listen once you talk to them about it. It’s been very positive at Stanford, and there is a lot to do on campus.”

Her 86-page book includes a child who writes stories about people in Syria. “She feeds the box with her thoughts; she puts in everything she has. She doesn't know it but her box becomes powerful. It takes up every word, every smile and every heartbeat and slowly, quietly, it grows. It grows into something so much bigger and more profound than she is. She’s just a child. She’s just a child who promised she’d save another but who doesn't know how. But one day, she looks at her box and she understands,” writes Abdullah, who will major in political science.

'It's a sad picture'

The Syrian civil war began in March 2011; the politics involved were not understandable to Abdullah. Would things return to normal? They did not, and have not since. She soon began losing friends – she estimates at least 20 people -- as thousands of children were tortured and killed. She wanted to do something and make a difference, and not just be a bystander staying silent. So Abdullah began expressing her thoughts and feelings in story form.

Regarding the book’s front cover, Abdullah recalled that when she told the child who drew it how beautiful it was, the child replied, “Don’t lie, it’s a sad picture.” Despite the bright colors, one sees children in that drawing crying and a military airplane flying overhead dropping bombs. And, one of the girls pictured, Nour, is lost forever, likely dead, noted Abdullah.

In one story, “Call of the Jasmine,” a little boy named Karim writes an early letter to Santa Claus, worried that he may not be alive come December. “I know where I live is not very pretty and I know there’s not much in it for you, but mama says we’re beautiful where it counts.”

In another account, a child is given an injection of lethal poison. “Everything subsequently goes dark but I close my eyes anyway. The darkness will protect me.”

Some quotes from the book include, “When you write something down, it stays forever. It's like a little part of you that you're giving to the universe.” Abdullah also writes, “We live in a world where some people have already lost the game before having begun.”

As she describes the experience of war on children, “There is no Richter scale to measure pain; it leaves you vulnerable. It's not pain you can get used to, not sorrow that you can tame. It leaves you broken, broken but alive.”

Ultimately, one of her characters said, “Maybe life just wants to be noticed, like a sulking toddler, so it will keep throwing things our way until we finally give it the attention it deserves.”

Disconnected world

Abdullah says literature and art allow us to connect with each other in ways that any other medium would really struggle to match.

“We tend to think of refugees as statistics; death tolls in faraway lands we will never live in. We see children of war and never picture our own for we assume that we will never find ourselves packing up our lives and everything we know only to cross oceans for new homes that do not want us,” she said.

That disconnect is the greatest part of the problem. “We allow ourselves to feel distanced from these events and these people. I wonder how many people stop to think ‘this could be me,’” she said.

Abdullah said that when people read a story or watch a play, they are able to think beyond their own lives and feel what another’s pain is like.

“If stories and theater allow us all to live the harrowing life of a refugee, if only for just an hour, maybe we could all carry a little part of them inside of us and maybe then we’d want to push for change,” she added.

‘Community and unity’

President Trump’s recent travel ban for Muslims from seven different Middle Eastern countries has focused attention on Syrian refugees, Abdullah said. Now, media outlets are interviewing refugees and doing in-depth stories on them. She believes the protests and activism around the country and on campus reflects the desire by many to take a closer look at the victims of the Syrian war.

“We see a greater sense of community and unity, and people who might not have cared about these issues are starting to do so now. People are saying, ‘this is not right’ There is a sense of hope,” she said.

She said that living in constant fear of being hurt by others for what you believe in and in fear of being told you can no longer enter a country like the U.S. is something no one should have to experience.

“Nobody chooses where they are born,” Abdullah said.

“My friends in the Middle East are afraid that all the years they have spent working hard will amount to nothing if their education is interrupted. Those studying in the U.S. wonder whether they will be able to visit their families for the holidays and those in other countries are afraid that maybe the ban will spread to where they are, too.”

Power of writing

Abdullah said she’s always enjoyed writing; she started publishing when she was 13, and has written for student newspapers and magazines in her home country. “I saw that people were being touched, and thought it could have an effect.”

Emma Abdullah

Emma Abdullah

Abdullah went to high school at the New English School in Kuwait. Her book has been adapted as a play by Alison Shan Price. Titled, “The Blue Box: The Memories of Children of War,” it premiered in Kuwait in 2015 and then internationally at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in Scotland last year.

For those seeking to help, Abdullah suggests making donations to the Syrian American Medical Society, which has helped with evacuations and humanitarian relief for children and others caught up in the crisis.

“The most important thing is not to forget them and not to allow anyone else to either. It is too easy to become indifferent, she said.

The Syrian war has dragged on for six years now, Abdullah said, and children continue to suffer and die every day.

“On a very small scale, the best thing you can do is talk about them and make sure your friends do, too. Learn more about the war and the refugee crisis so that you can spread the word,” she said.

People can donate to charities and NGOs that work with refugees, volunteer at charities, or even start their own fundraisers.

“Advocacy is crucial,” Abdullah said. “Protest, email or call your representatives and urge your government to increase their assistance to Syrian refugees, and encourage your friends to do the same.”

Follow CISAC at @StanfordCISAC and www.facebook.com/StanfordCISAC.

MEDIA CONTACTS

Clifton B. Parker, Center for International Security and Cooperation: (650) 725-6488, cbparker@stanford.edu