China's Risky Middle East Bet

China's Risky Middle East Bet

China is making a risky bet in the Middle East. By focusing on economic development and adhering to the principle of noninterference in internal affairs, Beijing believes it can deepen relations with countries that are otherwise nearly at war with one another—all the while avoiding any significant role in the political affairs of the region. This is likely to prove naive, particularly if U.S. allies begin to stand up for their interests.

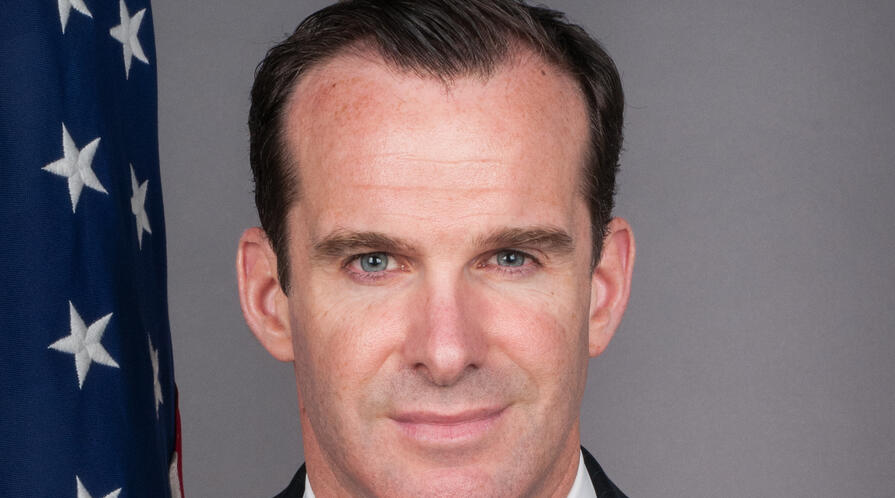

In meetings I attended earlier this month in Beijing on China’s position in the Middle East, sponsored by the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center, Chinese officials, academics, and business leaders expressed a common view that China can avoid political entanglement by promoting development from Tehran to Tel Aviv. China may soon find, however, that its purely transactional approach is unsustainable in this intractable region—placing its own investments at risk and opening new opportunities for the United States.

Over the past three years, China has charted an ambitious future in the Middle East by forging “comprehensive strategic partnerships” with Iran, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. This is the highest level of diplomatic relations China can provide, and Beijing believes these four countries anchor a neutral position that will prove more stable over the long term than that of the United States. China has also made massive investments in infrastructure throughout the region, including in Israel, where China is now the second-largest trading partner behind the United States.

China’s interests in the Middle East are both structural and strategic. Structurally, China needs the natural resources of the region, whereas the United States—now the world’s largest oil producer—does not. China is also seeking new markets to absorb its excess industrial capacity, and sees the Middle East poised for growth after decades of wars, woeful infrastructure, and popular discontent. Strategically, together with Russia, China is taking advantage of the uncertainty produced by ever-shifting U.S. policies, including zero-sum prescriptions for Iran and Syria that are unlikely to produce desired outcomes anytime soon. Regional governments in turn have welcomed China’s embrace, and its offer of investment without pressure to politically reform or respect human rights.

China’s President Xi Jinping previewed this more assertive Middle East strategy in a landmark address in Cairo three years ago. There, he declared that China does not seek a “sphere of influence” in the region—even while sinking nearly $100 billion in investments there through ports, roads, and rail projects. He alleged China rejects “proxy” contests—even while concluding a strategic partnership with Iran, the main sponsor of proxies in the region. And he warned against “all forms of discrimination and prejudice against any specific ethnic group and religion”—even while reportedly forcing 1 million Muslims into reeducation camps in China’s Xinjiang province.

Such contradictions can be maintained only so long as traditional U.S. allies in the region now welcoming Chinese investment allow them to be maintained. These U.S. allies do not shy from asserting their broader interests with Washington or expressing disagreement where policies diverge, and it is time they do the same with Beijing.

As the United States questions Chinese investment and intentions, particularly in the areas of technology and ports such as Israel’s Haifa, it can also challenge traditional allies as to whether they are granting China a free ride on what remains a largely U.S.-led security architecture. Such an arrangement should be as unacceptable to American partners in the region as it is to Washington. At the very least, these partners, together with Washington, can demand that Beijing utilize its emerging influence—particularly with Tehran and Damascus—to pursue measures that promote longer-term stability.

Read the rest at The Atlantic.